Filmmaking in the COVID-19 Era

Throughout 2020, I was privileged to be on the set of a few local, indie films – some shorts and one feature-length, including one of my own that I made in collaboration with some friends from school. My role has chiefly been a behind-the-scenes photographer, but I’ve also done some acting and shot B-roll footage (footage that is supplementary and is secondary to your primary footage of the subject). Beyond the sets I’ve done some graphic design, creating posters to promote the films (seen below), as well as some press release writing to help get the word out.

At this point, I’m barely even sure what it’s like to be on set without COVID protocols. I had helped with some other friends’ films in the past, in addition to my best friend’s father-in-law’s film (who was also my adjunct instructor for a couple screenwriting classes at the University of Southern Maine, because Maine is a very small state and life can be ridiculously serendipitous), but very briefly. And how very strange it all is, indeed.

I’ve now been on the set of five different films in the last year, all quite different from one another in theme and scope, and even in COVID policy.

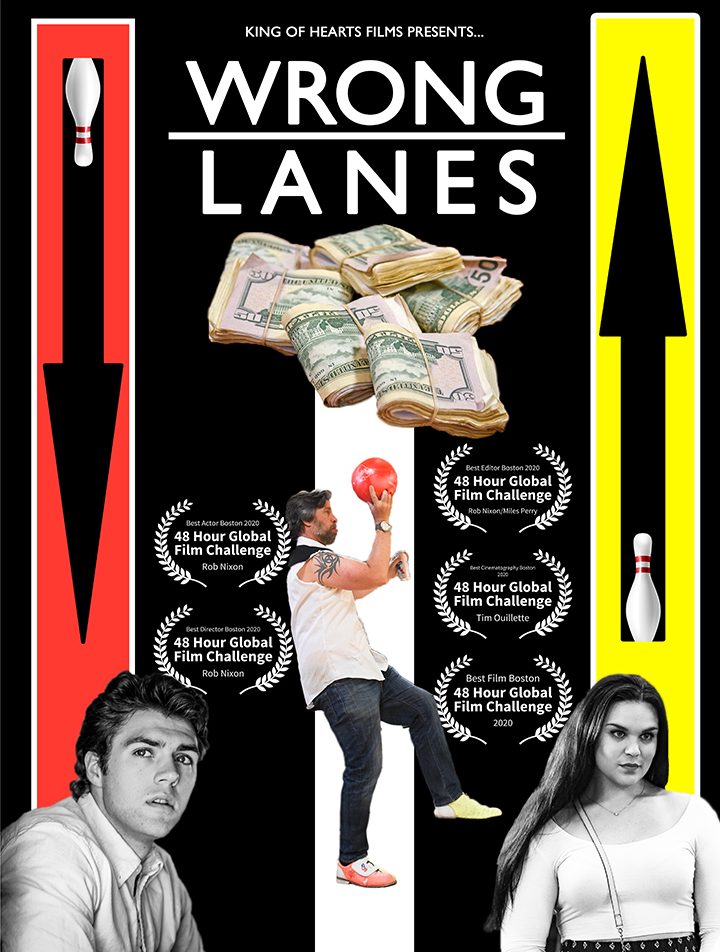

The first one was “Wrong Lanes,” made in collaboration with King of Hearts Films in South Portland and Munjoy Hill Media in Portland. It was filmed in Brunswick, Maine in just one day for the 48 Hour Film Festival, an international festival that inspires filmmakers everywhere to make an entire 5-10 minute film within just one weekend. Each registrant is given a theme, prop, character, and line of dialogue to incorporate. Then, the films are submitted before the weekend’s deadline to compete with other films in a region, and the winner then advances to the national competition and, finally, the international competition.

Poster for “Wrong Lanes,” shot in June 2020. Designed by Garrick Hoffman.

“Wrong Lanes” was filmed at the beginning of June, just two months or so into the lockdowns in the states, by a cast and crew of about 10. There was no budget at all, and the participation was completely voluntary – no one got paid for it. It was simply for the experience, the challenge, the joy and the fun of filmmaking with a group of creatives. We all discussed social distancing and masks on a Zoom call one night just days before the filming took place. Ultimately, COVID tests and masks were not required nor enforced; only one person chose to wear a mask, but it was very inconsistent. He was the DP (director of photography), but because he also had a small role in the film, he couldn’t have worn a mask at all times even if it was his preference to do so.

Thankfully, there were no stories of COVID among the cast nor crew in the days or weeks that followed. The only stories that came of it were in the newspaper and on television – but that’s because our team won the Boston region of the contest!

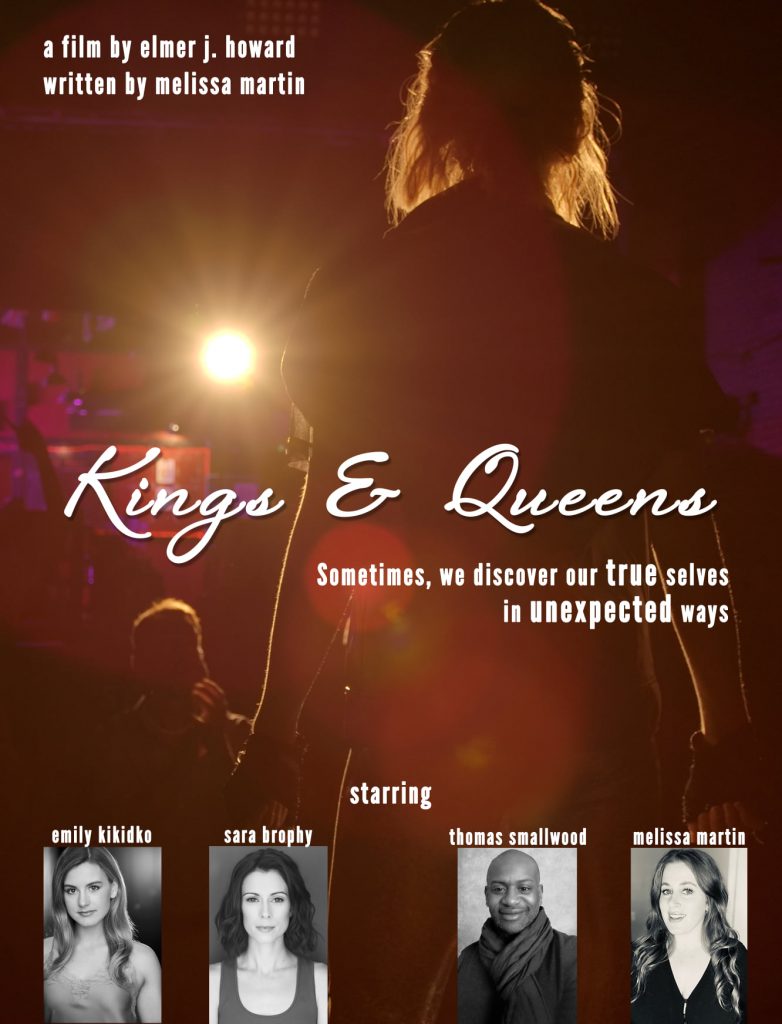

The next film was Kings & Queens, shot in Portland over three days in August with a bigger cast and crew, as well as an actual budget. Thrive Productions, owned and operated by Elmer Howard, produced the film and actually had a more fastidious and “legitimate” way of going about the filmmaking process. All participants were required to sign documentation and get a negative COVID test within – ideally anyway – 72 hours of the first day of production. Furthermore, the crew – meaning the director, camera and boom operators, gaffer (lighting guy), makeup artist, and myself – were required to wear a mask at all times. The cast – a.k.a. the talent, or the actors – were required to wear a mask whenever they weren’t actively shooting a scene. Upon arriving for the day, everyone was required to have their temperature checked.

Poster for “Kings & Queens,” shot in August 2020. Designed by Garrick Hoffman.

Hand sanitizer was generously distributed and available. There were always snacks, coffee and water available as well, but they were only accessible via a designated person with gloves who handed out the snacks per request. Meals were ordered by a local catering company, and they were always in the form of individually wrapped sandwiches, lest people get their fingers all over hypothetical pizza slices.

(“Hypothetical Pizza Slices” – that should be a band name.)

It was three days ranging from 10 to 12 hours with masks, and one of them was very, very hot as it was indoors and the air conditioning was off, presumably because it was at a bar that was not doing business, and because air conditioning units hinder the sound recording during film production. It made me think of what people like nurses go through, or people in other occupations who have to wear masks for similar lengths of time for even more days, each and every week. Masks honestly don’t bother me at all personally, and as a self-professed quasi-germaphobe, in some ways I welcome them. I know that not everyone can say the same, particularly those with beards that could rival a Viking’s. Or people with glasses, like me on days when I choose not to wear contacts and have to pay a visit to the grocery store. Grocery shopping with foggy glasses is hardly a margarita on a lake in the summer, I promise you.

One time, at the end of the first day, I was taking a break waiting for the next scene to finish being shot (I wasn’t allowed to be present because there was a large mirror and a lot of people in a tight space), and I had just finished having a snack. I inadvertently left my mask dangling from my ear as I sat at the bar, killing time on my phone, when a crew member politely asked, “Hey man, can you put your mask back on?” Embarrassed, I immediately returned the mask to its proper position. Aside from one time when I walked to the bathroom at a restaurant sans a mask over the summer, I think that was the only other time I’ve had mask-wearing enforced upon me. It was also a sign of how seriously it was taken.

As another sign of the seriousness of COVID requirements on this set, I later learned that the gaffer was working by himself for the first two days because his assistant didn’t get his test results back in time. When he finally got his results back – negative, of course – he was allowed on set for the third day.

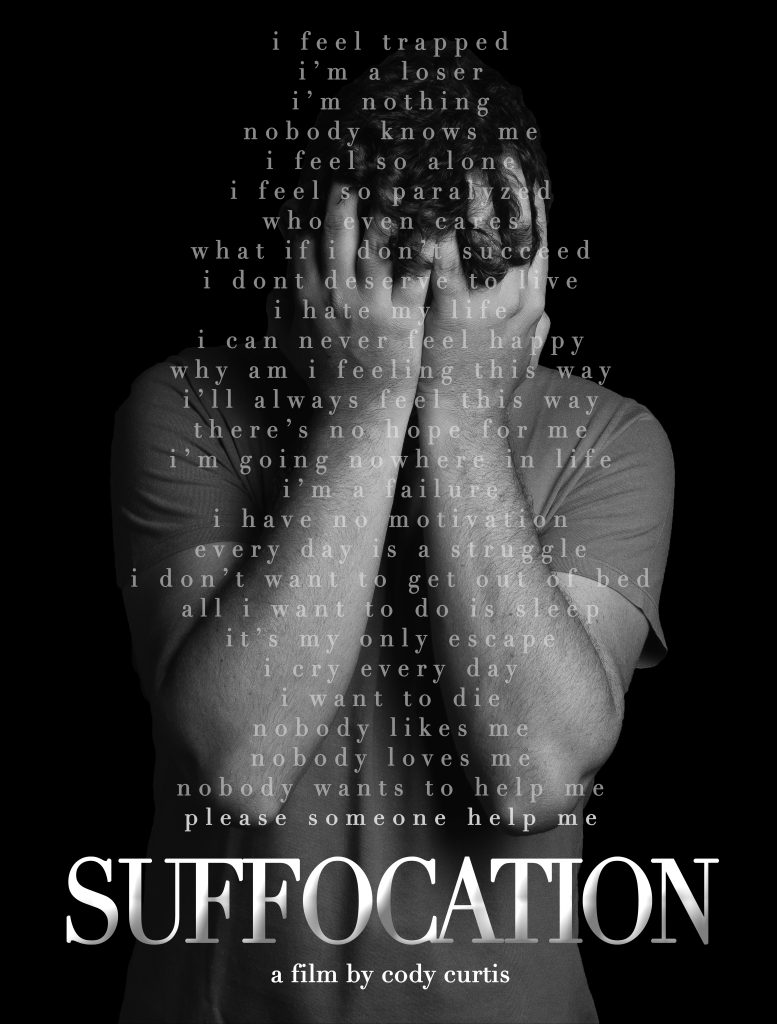

Just this month, I was on the set of my friend Cody’s feature-length film, “Suffocation.” Similar to “Kings & Queens,” Cody required everyone to receive negative COVID tests prior to the first weekend of filming, checking in at the beginning of each day of filming to have temperatures checked, masking up at all times (again, save for the talent when filming), and having a designated food distributor (who was also required to wear gloves). For this film, I did chiefly behind-the-scenes photography (known as “stills” or “unit” photography in the film world), as well as a small scene acting. The scene I was in was the only time I was permitted to remove my mask.

Poster for “Suffocation,” shot in Maine in October 2020. Poster design by Garrick Hoffman.

This is how accustomed we’ve become to wearing masks at this point: Sometimes, on “Kings & Queens” and “Suffocation,” a scene would begin to be filmed, and then seconds or even minutes later, we’d hear, “Cut!”

The reason? The actor or actors forgot to take their masks off for the scene.

“Okay, from one!” the director or assistant director would bellow, meaning restart the scene from the beginning.

At the end of October, I had a small role in a horror film written and directed by a guy I met on the set of “Kings & Queens,” Mark Parker. I played the role of a ghost, and did some BTS photos and videos in between scenes.

To get an idea of how Mark approached COVID protocols, here’s what part of his email read in the week leading up to the shoot:

“When you arrive, please text me. Please wear a mask. I’ll take your temperature and give you your own individual hand sanitizer and a fresh disposable mask. Please use your sanitizer throughout the day, making sure you sanitize your hands before and after using the bathroom every time. Actors, you’ll be asked to wear a mask in between scenes/setups. Throughout the day, I will wipe down high-touch areas inside and outside of the cottage. Please do your best to not touch things inside the cottage unless you have to.

“Holding: Because of Covid and our tiny shoot location, please use your car as your own holding area as much as possible. Occasionally, some of us will be able to use the cottage for holding, but that won’t always be the case.

“Attached here is an appearance release form for our short film TWIN. Instead of having you do this on set tomorrow and sharing pens, can you please fill in your name, role, e-signature, and date, and either send it back to me as a PDF, screenshot, or picture?”

Like the rest of the cast and crew, I was also required to get a COVID test, of course. But I mistakenly got it just two days before the shoot, unsure whether I’d even get my results back in time for the film. Because I had to shoot a scene that calls for not wearing a mask, Mark made the unfortunate decision to play the ghost himself and have me come to shoot BTS and maybe assistant direct in the event that I couldn’t get my results back in time.

However, the morning of the shoot, I got my results back: negative!

“Haha amazing!!! I had a feeling we’d find out in the morning,” he responded to the good news. “What a relief.”

Both “TWIN” and “Suffocation” are still in the middle of post-production. “Kings & Queens” has finished its post-production phase, but won’t be released until the spring or summer, I surmise.

Even beyond the little filmmaking sphere here in Maine, I’ve been reading how COVID has affected productions of large-scale, big-budget, Hollywood-backed films with crews in the hundreds – or more. It may be “easier” to manage COVID policy and enforcement on a small-scale, small-budget indie film, but how is it managed on a Hollywood scale?

From what I’ve read, COVID protocols are quite similar to small indie film productions, but with some things taken a bit – or significantly – further. For example, while there have been COVID officers in some form or another on the sets I’ve worked on (the ones who take temperatures at the beginning of each day), it sounds like the COVID officers in the entertainment industry actively police social distancing, and on some (if not all) sets, testing is administered every single day.

Furthermore, instead of crew members freely mingling, they’re being divided into “pods” that limit how production departments such as wardrobe or lighting can associate, established “Zones” dictate where those cast and crew can go, and large crowd scenes – like the one in Braveheart with 1,400 extras – are a no-go now, according to an article in the Washington Post. (This article has many more details – check it out to learn more.)

If you want to get an idea of how seriously COVID is taken in Hollywood, I recommend you watch this video of Tom Cruise absolutely drilling into the cast and crew for allegedly violating COVID protocols.

COVID has also affected other matters in filmmaking & entertainment. Actor Robert Pattinson, the star of the upcoming film “The Batman,” tested positive for COVID in the middle of the film’s production, derailing its schedule and no doubt costing the studio heaps of money as he quarantined for two weeks. Additionally, the shift to streaming is complicating the industry and has resulted in the closure of at least one movie theater company, such as – quite tragically – all the Cinemagic theaters here in Maine and in New Hampshire. An exasperated Christopher Nolan, the famous director behind “Inception,” “Interstellar,” and the Christian Bale Batman trilogy, notoriously denounced HBO Max and Warner Bros. for their straight-to-streaming plan in lieu of the uncertainty of the future of theaters.

Mark Parker directing on the set of his film, TWIN

A fun self-portrait on the set of TWIN

Ultimately, even with my limited experience on film sets, I can tell you it’s a surreal time to be in entertainment. COVID has completely transformed the way films and television (and beyond) are executed. But just like many industries – food and beverage or hospitality for example – there’s simply no way around it, and we can’t expect these industries to simply cease operation because of the virus. Other industries are hurting far worse, like the beloved live music industry (one of my favorites, personally), which after a year since the beginning of quarantine and lockdowns, is still not operating at all.

The only way to navigate operation is taking every conceivable cautionary measure to ensure the safety and health of all participants, which is what seemingly all film productions – indie or Hollywood – are doing, and quite aggressively, evidently. It no doubt creates a myriad of challenges, but the only other option is shutting down completely, which is untenable.

Who knows what the future holds for the film industry, but for now, filmmaking has entered a new dimension with how productions are executed. Thankfully the COVID vaccine has offered a glimmer of hope, and things are already beginning to change nationwide for the better, it appears.

Are you a filmmaker? If so, what’s it been like to produce films during the pandemic? Do you have any questions about filmmaking during the COVID-19 era? Leave a comment below!

Leave a comment!